On the first outbreak of the deportation she was exiled with her parents and two brothers in the direction of Deir el-Zor. Traveling afoot [from Aintab], they reached Meskene. After a few days rest, the caravan started again for Deir el-Zor. On the road, the poor people were exposed to the attack by a band of plunderers, who, like a pack of wolves, descended upon them, robbed, and killed the people at their pleasure in the presence of the gendarmes, who, after the slaughter, shared their plundered booty. Loutfie’s mother fell dead in the way of guarding her young ones. Her father and younger brother fell too. The older brother was lost and she herself came into the possession of a Tchechen, who sold her to a Kurd, the later passed her to a rich Turk named Mahmoud Pasha who sent her to his house in Veranshehir.1 There she remained for 11 years till she got the opportunity to cross the border to Ras el-Ain from whereby our Hassitche [Hassaka] agent she was sent to us. Fortunately, on the day following her arrival, we gained information of her lost brother who had been at Marseille until a few months before. We shall take care of her until we succeed in locating her brother.

Left our care on May 19, 1926. Relatives, uncle in Aleppo2

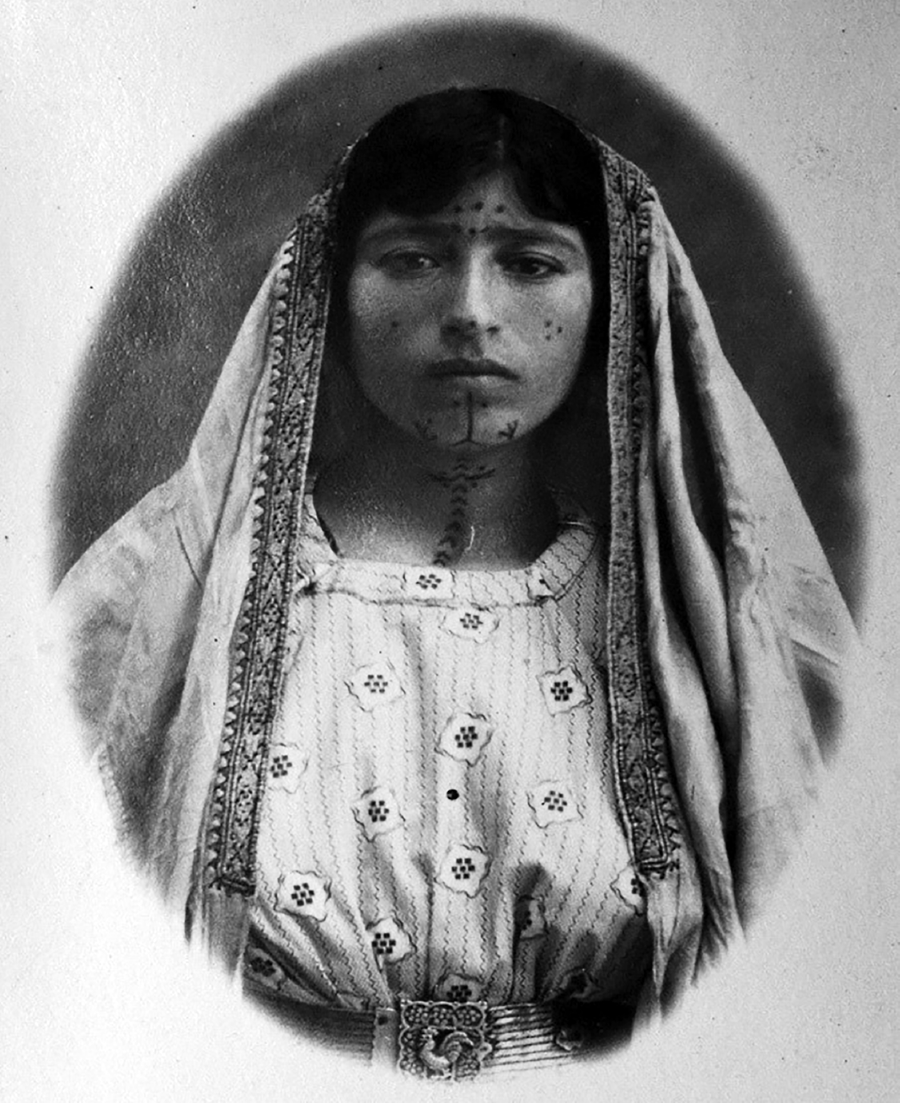

Loutfie Bilemdjian’s story was transcribed when she arrived at a Rescue Home ran by Danish humanitarian and League of Nations commissioner Karen Jeppe (1876–1935) in the spring of 1926. The entry provides a brief sketch of her ordeal as she was passed between men who bought and sold her near Dayr al-Zur, Syria. Loutfie was finally sold to a wealthy Turk in Viranşehir, a small town located between Urfa and Mardin in today’s southeastern Turkey. Trafficked between a triangle of cities where the buying and selling of human cargo was heavy during the Armenian Genocide, Loutfie’s image circulated along with those of other victims in European and American appeals for humanitarian aid funding. To audiences, her tattooed face spoke for itself as indelible proof of her enslavement and her experience as a “trafficked woman,” in the human rights parlance of the period.

Loutfie’s beauty is stunning. She surely attracted the eye of both slaver and humanitarian, but there is something particularly striking about the photograph taken in the studio adjacent to the Rescue Home office and later cropped and pasted to Loutfie’s intake register. Many other women and children who appeared in that studio recoiled before the camera, its penetrating lens aimed at their battered faces and bodies to visually communicate the trauma described in the textual narrative. Loutfie, however, appears to sit comfortably before the photographer, meeting the camera’s gaze. Other runaways wore tattered clothing—a tuft of fur for a shawl, rags for clothing. Loutfie, by contrast, is well-dressed, more proof that she was kept in an elite household. Perhaps she felt a tinge of shame about her tattoos, but instead of hiding her face, she pulled her embroidered cloak up over the back of her head for a degree of modesty before the camera.

For me, the intricate chicken belt buckle, perhaps carved from bone, stands out as a symbol of the care this young woman took in her appearance. Such care is affirmed again when I notice that the  pattern tattooed on Loutfie’s face is echoed in the dots and geometric designs on the dress she likely sewed herself. In the unusual case that another woman embroidered her garment, Loutfie still would have had some hand in the design work. The crow’s-foot design that runs down her neck and chest is suggestive that the tattoo design may continue under her dress to possibly form the hayat ağacı, or “tree of life” motif.3 Some versions of this motif encircle the breasts and extend all the way to the groin area and intend to offer its wearer blessings of a long, healthy life.4

pattern tattooed on Loutfie’s face is echoed in the dots and geometric designs on the dress she likely sewed herself. In the unusual case that another woman embroidered her garment, Loutfie still would have had some hand in the design work. The crow’s-foot design that runs down her neck and chest is suggestive that the tattoo design may continue under her dress to possibly form the hayat ağacı, or “tree of life” motif.3 Some versions of this motif encircle the breasts and extend all the way to the groin area and intend to offer its wearer blessings of a long, healthy life.4

Unmentioned in the entry are Loutfie’s tattoos, which tell us aspects of her story that we might miss without closer observation. The dot on the tip of her nose and the .¦. pattern on her chin indicate that she was captured somewhere between Ras al-‘Ayn and Dayr al-Zur by the Wuld Ali, a tribe that constituted part of the ‘Anaza confederation.5 Transferred between three men—a Chechen, a Kurd, and a Turk—the details of her time among the ‘Anaza is documented on the skin of her face rather than the written record. Observing these silences, I wonder, what other silences are there in the archive? What other ways might I view, read, and listen to archival documents for the minute traces of genocide experience?

In this book, I analyze the fragmentary evidence of Armenian survivors, paying special attention to the traces violence and memory have left upon the body of the archive and the actual bodies of Armenian victims and their descendants. The embodied trauma of victims of sexual abuse and forced marriage have been, at times, deemed too personal and too emotional to be worthy of historical study. Many stories have been held tightly as familial memories, while others have fallen into oblivion over time—this is most true for male victims of sexual abuse, whose stories have yet to be told. The story of sexual violence, while central to the objectives of genocide, are often relegated to a single-page mention within the existing historiography. But in the pages that follow I argue that thinking through and with the materiality of the body—as an archive of genocide experience that communicates emotional and affective knowledge discarded by the violence of traditional archives—can unlock traces of historical evidence that are worthy of study. By highlighting these ciphered bits of information, what I call remnants, I situate the material body of survivors as a repository of traumatic experience, bodies that also form sites of resistance where the memory of victims are preserved by their descendants.

Claudia Card has argued that genocide is an attack on “social vitality,” the vibrancy and cohesiveness that “exists through relationships, contemporary and intergenerational, that create an identity and gives meaning to life.”6 Stamping out this vitality through cultural genocide and forced assimilation produces social death for the target group. In the case of Armenian women, they were most vulnerable to Islamization since Muslim patriarchal order and sexual regulations in Islamic law facilitated the assimilation of non-Muslim (dhimmi) women. For the Armenian diaspora, the tattoos that some women survivors bore have largely come to signify the shame of Islamization, mysterious visual artifacts from the largely successful attempt to eliminate the Ottoman Empire’s Christian population from its eastern provinces.7 Yet, the tribal tattoos themselves hold no religious meaning within Islam. The tattooed survivor is presented as a living (ethno)martyr within recent documentaries, while at other times a national stain, her tattoos a memory of the successful core genocide campaign to eradicate Armenian identity in historic Armenian homelands.8 Occasionally, counternarratives disrupt our received wisdom by portraying the tattoos as badges of heroism and survival.

The women and children who survived the violent ethnic cleansing campaign are still referred to pejoratively in Turkey today as the “remnants of the sword” (kılıç artığı), those who were deported, raped, enslaved, and forcibly assimilated into Muslim households.9 The sometimes incoherent fragmentary wreckage of what was once the Ottoman Armenian community is also referred to as “remnants” (Armenian: khlyagner, pegor, or mnatsorats) by Armenian contemporaries.10 In the ruminations of Giorgio Agamben, remnants lie at the disjuncture between the drowned and the saved; they are the attempt to listen for the gaps in survivor testimony and reckon with the impossibility of witnessing for the true witness is already dead.11 I seek to reclaim the concept of remnants as a tool of resistance against post-genocide aphasia and to locate the bodies of Armenian women and girls that have miraculously survived within a mutilated historicity.12 Some texts are shared in their raw form between the chapters of this book as a means of drawing attention to both absences and traces that linger despite the state’s attempts to erase them.

As I reflect on my family’s trade as tailors, I am inspired by how the original terminology for text in Latin originates in the verb root textere, meaning “to weave”; the text itself is a series of threads that form a woven textile. Remnants are texts, but they are also bodies. Fragmented bodies, individual and communal, were disassembled in the process of genocide, a process I call dis-memberment. The bodies of victims were reassembled by humanitarians and nationalists after the war to recover remnants of the Armenian community. Visual, written, oral, and bodily texts of survival are fragmentary yet remain historically valuable for the information they contain. Rather than assigning these bits of fragmentary wreckage secondary status, I give them center stage to break open the archival record to offer an alternative reading of genocide experience.

Remnants are also immaterial traces of psychic intergenerational trauma as descendants grapple with fragmentary postmemory: secondary traumatic memories that are not rooted in personal experience but have instead been transmitted through image, narrative, and storytelling to form a range of communal memories. A fitting parallel is the transmission and remembrance of Holocaust postmemory, as Marianne Hirsch and Leo Spitzer explain of the Jewish survivor community:

These events were transmitted to them so deeply and affectively so as to seem to constitute memories in their own right. Postmemory’s connection to the past is thus mediated not by recall but by imaginative investment, projection, and creation.13

The capacity for postmemory to form personal recollections helps us understand how it is that community members who did not directly experience genocidal trauma experience carry memories of dis-memberment, tattooed skin, and bones in the unmarked killing fields of the Syrian Desert. These memories are not shared for what they can offer empirically but instead for what reveal about the emotional weight of genocide that extends beyond the event itself—the genocidal erasure of Armenians from their ancestral homelands is ongoing.

Rather than use the term postmemory, I’ve chosen to use the term prosthetic memory to describe the intergenerational and mediated transference of shared memories and stories because the term captures how memory is an embodied practice.14 Memory is stored within the body and genocide is remembered as body horror in which victims are forced to witness extreme violations of the body and desecration of the corpse. Furthermore, prosthetic memory15 captures some the historic connection between memory and ritual in premodern human history, especially among Christian communities where the Eucharist, fasting, vespers, self-flagellation, and pilgrimage were embodied, temporally situated memories of Christ’s suffering. Within ancient societies, human archives were people who were living, breathing repositories of memory, who embodied the religious and cultural texts they had memorized. Memory in our modern mediated culture works similarly, as historian of memory Alison Landsberg explains:

Of course, this modern form of memory—prosthetic memory—shares certain characteristics with memory in earlier historical periods. With prosthetic memory, as with earlier forms of remembrance, people are invited to take on memories of a past through which they did not live. Some of the strategies and techniques for acquiring memories are similar, too. Memory remains a sensuous phenomenon experienced by the body, and it continues to derive much of its power through affect.16

Philosopher Maurice Halbwachs claimed memory is socially constituted to the extent that individuals draw upon the “group memory” transferred to them by others. While historically this transfer of memory occurred through storytelling, text, and church and state ritual, twentieth- and twenty-first-century media has greatly amplified and expanded group memory transmission.17

The age of mass media allowed for broad dissemination of printed and oral Armenian narratives of survival to the broader Armenian diaspora. The Armenian Genocide, like the Great War, occurred at the dawn of a new era of media-fueled prosthetic memory formation. That era continues today in the internet age, as stories of the genocide are broadcast with speed and breadth to audiences that extend beyond the Armenian community. Films, documentary journalism, and print and digital media—much of it authored by Armenians—continue to explore the legacy of the Armenian Genocide and make stories about it available to a wider audience. Over the last century, the memory of the Armenian Genocide has lived on, in part, through the transmission of memory through mass media, social media, and the internet, allowing it reach audiences beyond a single ethnic, racial, or religious grouping.

Prosthetic memory, as I see it, links past and present, and in the case of the Armenian Genocide, it opposes the uniformity of official memories shaped by the nation-state through violent erasure. Because the Ottoman Armenian community is now a diaspora dispersed across several nation-states (including Armenia), some memories lack official sites of memory and state monuments. These memories are what historian Mériam Belli has called “historical utterances,” the messy, unofficial, and even at times unstable or inconsistent memories that lie outside official accounts.18 Like phantom limbs of the amputee, prosthetic memories are still present and felt by subsequent generations by means of their engagement with the past through witnessing, storytelling, and memory work during pilgrimages to sites of mass atrocity. It is within this affective state that new knowledge is constituted. I honor these dissonant memories while also interrogating them for the stories they can tell us about embodiment and genocidal loss. Because the stories I share often fall outside the purview of state archives that have largely obliterated the voices of victims, it is important to share with the reader that I have a bone to pick with the archive.

1. Viranşehir, as one survivor, Zabel, recalled, was where “they collected all the beautiful girls, and distributed them.” “Registers of Inmates, the Armenian Orphanage in Aleppo,” 1922–1930 (hereafter “Registers”), inmate 961, March 25, 1926, United Nations Archives (UNA) at Geneva, Switzerland.

2. Loutfie Bilemdjian’s story is shared in “Registers,” inmate 1010, May 17, 1926, UNA. I have retained the original errors in English and spellings in Jeppe’s own handwriting to retain the authenticity of the account. The account was composed in Jeppe’s Reception Home in Aleppo, which was also referred to as Jeppe’s Rescue Home. These records have been recently translated into Turkish in an important volume edited by Dicle Akar, Matthias Bjørnlund, and Taner Akçam, Soykırımdan kurtulanlar: Halep kurtarma evi yetimleri (İstanbul: Iletişim Yayınları, 2019).

3. In a fitting parallel with Loutfie’s gown, tattooed former Indian captive Olive Oatman, whose story is shared in chapter 8, also wore a dress that suggested a hidden arm tattoo. Though the tattoo was never photographed, the arm embroidery on her gown hinted at the tattoo and likely emulated its design. See Margot Mifflin, The Blue Tattoo: The Life of Olive Oatman (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009), 158.

4. Uysal Yenipınar and Mehmet Sait Tunҫ, Güneydoğu anadolu geleneksel dövme sanatı beden yazıtları (İzmir: Etki, 2013), 214–15.

5. Because there are few studies of tattoos within Syria, I drew on correspondence with a seasoned anthropologist of Syria, Dawn Chatty, who has worked among the tribes for over four decades. Through this correspondence she explained how a combination of tattoos represented specific tribal affiliation in Loutfie’s case. Dawn Chatty, email correspondence, April 25, 2017.

6. Claudia Card, “Genocide and Social Death,” Hypatia 18, no. 1 (Winter 2003): 63.

7. A recent book has argued that the Ottoman Empire orchestrated a genocide against all Ottoman Christians rather than Armenians specifically. See Benny Morris and Dror Ze’evi, The Thirty-Year Genocide: Turkey’s Destruction of Its Christian Minorities, 1894–1924 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2019).

8. Understudied, tribal tattoos have appeared in recent documentaries and exhibits, often accompanied with little context. See Bared Maronian, dir., Women of 1915 (2016); and the Armenian Genocide Museum Institute’s online exhibition Becoming Someone Else . . . Genocide and Kidnapped Women. By contrast, Suzanne Khardalian’s film Grandma’s Tattoos (2011) provides more context to the tattoos through its ethnographic engagement with Syrian Bedouin.

9. Fethiye Çetin, Anneannem (Istanbul: Metis Yayınları, 2004) 81. Çetin’s work was crucial to generating a discussion about Armenian grandmothers within Turkey. Subsequent to the publication of the memoir was the publication of a volume edited by Çetin and Ayşe Gül Altınay, Torunlar (Istanbul: Metis, 2009), later translated into English as The Grandchildren: The Hidden Legacy of “Lost” Armenians in Turkey (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2014). One contributor to the edited volume, filmmaker Berke Baş, released a documentary about her Armenian grandmother titled Chanson de Nahide (2009).

10. In Armenian, khlyagner (խլեակներ) can mean “wreckage,” “fragments,” or “remnants” of the uprooted and exiled Armenian nation. A word with similar meaning forms the title of an important novel by Hagop Oshagan, Mnatsortats, (Antelias, Lebanon: Dbaran giligioy gatoghigosutean, 1988). See Keith Watenpaugh on the term khlyagner in Bread from Stones (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2015), 14–15.

11. Giorgio Agamben, Remnants of Auschwitz: The Witness and the Archive (New York: Zone Books, 2000).

12. Marisa J. Fuentes, Dispossessed Lives: Enslaved Women, Violence, and the Archive (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016), 7.

13. Marianne Hirsch and Leo Spitzer, School Photos in Liquid Time: Reframing Difference (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2020), 14; emphasis mine.

14. Carel Bertram calls these shared narratives “memory-stories” in her recent study titled A House in the Homeland, 7–8.

15. I have borrowed the term “prosthetic memory” from Pierre Nora’s discussion of “prosthesis-memory” in “Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire,” Representations 26 (Spring 1989): 14; and Alison Landsberg, Prosthetic Memory: The Transformation of American Remembrance in the Age of Mass Culture (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004).

16. Landsberg, Prosthetic Memory, 8.

17. Maurice Halbwachs, On Collective Memory, ed. and trans. Lewis A. Coser (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992), 38–40, 53.

18. Mériam Belli, An Incurable Past: Nasser’s Egypt Now and Then (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2013), 3.